L.A.’s last country music radio station, after 25 years serving that market, switched formats August 17. If I seem a little slow on the uptake on this one, it’s only because I had no idea anything of the sort had transpired until Saturday, when I went for a haircut and was filled in on the news by my gay black West Hollywood hairdresser, who’s despondent over the loss.

“When I went out for coffee the other day I heard strains of Carrie Underwood and started following the SUV she was coming from,” he said, doing a little Frankenstein monster walk to illustrate his blind desperation.

When I asked what format the station had switched to, he spat, “Hip-hop R&B crap,” then he joked that his “people” were after him, that they’d heard about some black guy listening to KZLA and just wouldn’t stand for it.

My hairdresser certainly isn’t the only one in distress. “I almost threw up, I was so upset,” said longtime KZLA listener Ruth Rogers, according to the

Los Angeles Times. “I think it’s racist.”

Really, Ms. Rogers? What kind of racism would that be? The 53-year-old Orange County resident continued, “This is becoming a nation of minorities. I’m not going to turn on my radio anymore. Country music promotes patriotism and family values, and they’ve replaced it with something that just promotes money and hate.”

Oh, that kind of racism.

I’m not what I would call a country music fan, though I do like country music. I’m sure you get the distinction. The appellation “country music fan” just has too much baggage, an unpretty, jingoistic, Republican, NASCAR vibe. A Ms. Rogers, not-my-demographic vibe. So while I have a fair amount of classic country and country-influenced singer-songwriters in my music library, I hesitate to tell anyone that I like country music.

In truth, I was raised on the stuff, back when Southern California had any number of stations to choose from. My mom leaned toward KFOX, which played a mix of contemporary and classic country, and our radio was always on. Always—even when everybody was watching TV. It was all I knew for years. Very much like Chinese food in China is just “food,” country music to me was “music,” and as a kid I loved calling the radio station with special requests, first asking Mom what she wanted to hear then ringing them up. I was put on the air a few times, probably because the DJ thought it both disturbing and cute that a kid was asking for songs with titles like “Barrooms to Bedrooms” (among my mother’s souvenirs there’s a cassette tape of me requesting this very song, recorded straight off the radio with my boxy portable cassette player).

Through both subliminal and active processing, I absorbed quite a lot, and I can sing you a startling number of 1970s country songs, a talent on display this weekend as my partner witnessed the full extent of my childhood inculcation into the country music fold.

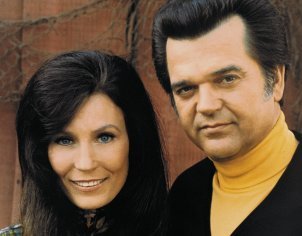

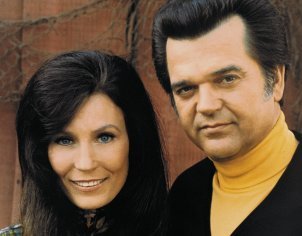

“You don’t remember ‘Louisiana Woman, Mississippi Man’? Conway and Loretta?” I asked, with the proper amount of shock, then tried to jog her memory by singing the hook.

“Hey! Looziana woman, Mississippi man

We get together any time we can

Mississippi River can’t keep us apart

There’s too much love in this Mississippi heart

Too much love in this Looziana heart.”

Blank expression.

We were in her Little Blue Truck™, leaving a local shoppertainment center. Before lunch we had gone to one of my favorite

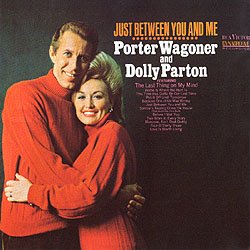

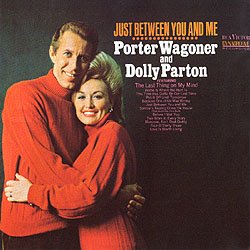

previously owned CD stores to search for the latest Hem album and a decent George Jones & Tammy Wynette hits package. Hem was swiftly located—and bargain-priced because the young people who work at the store have no idea who Hem is—but the only George & Tammy collection they had was a three-CD set, which I passed on. I’m not sure anyone needs that much G & T. After lunch I drifted into Tower Records, located at the aforementioned shoppertainment complex, in search of same. There were no George & Tammy CDs to be had, but I did emerge with hits collections from Porter Wagoner & Dolly Parton and Conway Twitty & Loretta Lynn. (Country convention demands that the man’s name be cited first.)

My present fixation with country music duets was sparked by the recent Mark Knopfler & Emmylou Harris album

All the Roadrunning. It’s been in my car’s CD deck for months, spinning down only on rare occasions, when even I have to admit that it’s becoming the aural equivalent of wallpaper. I’m a longtime Harris fan, so I was destined to like the collaboration—inasmuch as anything she touches rates somewhere between pleasant and transcendent on my very subjective scale of liking. As an Associated Press reviewer noted, “Emmylou Harris would sound good matched with a singing hinge.” He went on to dismiss the album as lacking chemistry. I couldn’t disagree more.

All the Roadrunning is one of those albums that took a few listens before I embraced it with ferocity, then I was surprised at how much I liked Knopfler’s songs—all originals—and vocals (his fretwork always being unassailable). But the way they came together with alternating sincerity and playfulness is what really won me, and their interplay reminded me of some of the great country duet partnerships.

Whatever happened to country music power couples anyway?

Through the 1970s, country radio was lousy with duets, and they weren’t isolated tracks from otherwise solo albums, they were from dedicated duet albums, from superstar singing partners who were often dating or married—making their songs of love and loss that much more resonant.

Remember?

If you don’t, you have something in common with my partner.

“How about George & Tammy’s ‘Two Story House’?” I asked, quoting its bouncy refrain: “ ‘How sad it is we now live in a two-story house.’ ”

“Why is it sad that they live in a two-story house?” she asked flatly.

“Because there’s no love about,” I said, solemnly. “They strove so hard for success, they had no time for each other and they fell out of love.” Then I broke into song again:

“I’ve got my story

And I’ve got mine too

How sad it is

We now live in a two-story house.”

Silence.

“You see,” I said helpfully, “they each have their own story about what went wrong, and they also each have their own

story.”

“Yeah, I get the complicated layers of meaning,” she said, with no small amount of sarcasm. “But no, I’ve never heard the song.”

“ ‘Golden Ring’?” I offered, not even pausing this time before singing the final chorus.

“Golden ring (golden ring) with one tiny little stone

Cast aside (cast aside) like the love that’s dead and gone

By itself (by itself) it’s just a cold metallic thing

Only love can make a golden wedding ring.”

I studied her face for a glimmer of recognition and found none.

“Sweetie, I didn’t grow up in your mother’s house,” she said.

For years I had been under the delusion that these songs were ubiquitous, part of our collective American experience, our national fabric. Come to find out, not everyone grew up under the unrelenting influence of country radio. Weird.

Weirder still, I had failed to notice the long, slow death of country radio in my own hometown.

“The Los Angeles radio market is basically 40% Hispanic, 11% Asian, and 8% black, and country fans are about 98% Caucasian,” said Rick Cummings, a top executive at KZLA’s parent company, Emmis Communications Corp., according to the

Times. “My job is to attract as large an audience as possible.”

And so it was that immediately following rush hour on the morning now known unironically as “Black Thursday” by KZLA listeners—who call themselves KZLAnation—the morning drive show DJ was reportedly told to segue from the Keith Urban track he was playing to a Black Eyed Peas song, after which he and his fellow staff members were

let go.I know from experience that format changes are as a rule executed unceremoniously. For three golden years, 1994–1997, 101.9 KSCA played an “adult album alternative” format that won my heart. For the first time since high school I felt like a radio station “got” me, that I was part of a recognized demographic who liked singer-songwriters and artists who blended elements of rock and folk and pop and soul and jazz and country into music that sometimes defied categorization and almost always ducked the top 40. Then one day I turned the ignition in my car and Spanish-language programming filled my interior; my little bright spot on the dial was gone forever.

While I understand that my piddling singer-songwriter demographic isn’t an advertising magnet, the death of country radio is more curious. Los Angeles reportedly accounts for 3% of all country music sales nationwide, making it the number 1 sales market in the genre for most major record labels. The very night KZLA crooned its last, Faith Hill and Tim McGraw played their first of three sold-out nights at the Staples Center: capacity 20,000. That’s a lot of cowboy boots for a supposedly urban market. Sure, on any one of those three nights I could likely have rolled a bowling ball from one end of the arena to the other without hitting a Democrat, but still, those folks deserve a radio station too. It placates them.

“What will all the Republicans listen to?” I asked my hairdresser.

“Now, now,” said my demographic-defying friend. “They’re not all like that.”

I couldn’t help but notice that when he talked about KZLA listeners and country music fans, he said “they,” not “we.”

Country music is appealing, I think, in a broader way than it’s marketed. The audience doesn’t

have to be 98% Caucasion, nor should anyone who likes country be made to feel like an outsider for being black or gay or Democratic or antiwar—or for not appreciating a goddamn car race.

I don’t miss KZLA, whose play list was dominated by your Tim McGraws, your Brad Paisleys, your Gretchen Wilsons—whoever was hot at any given moment. Even my mom had stopped listening to the radio long before the death of KZLA, her taste having gone completely retro. She’s resorted to a mail-order catalog (with no Web presence—

that old-school) called Country Music Memories, where she can purchase Boxcar Willie, Stanley Brothers, and Ferlin Husky CDs with abandon.

Me, I prefer your Donna Fargos, your Loretta Lynns, your Bobbie Gentrys, and to Tammy Wynette I guess I’d have to say, Tammy why not? So I do miss country radio, at least in theory. I miss the radio of my youth, when it was just “music.”

By the way, if anyone knows a gay country music lover in SoCal who’s available, my hairdresser is tall, fit, and handsome. He does a mean two-step, and he’s a Democrat.